I recently talked to Gary Monroe, the author of The Highwaymen and well known for his work on Florida photography. He suggested I publish his comments on my forty years of work on Florida art on this website. So…with thanks to Gary here is what he said.

What Alfred Frankel has accomplished is akin to what artists create. His work is an opus of art research and writing that clarifies Florida art’s origins. Frankel’s pioneering contribution established a baseline from which we can understand the development of painting in Florida. For more than thirty years, Frankel has scoured the libraries of the state, from Pensacola to Key West, from Florida State University, to the University of Florida and the University of Miami, in the stacks and looking at microfiche to understand the development of Florida painting. His labor resulted in a testament that informs nascent and seasoned collectors. Indeed, any view of Florida art would be incomplete without recognizing Dr. Frankel’s contribution. As Florida art grew so did the significance of Frankel’s work; as his work developed, the interest in Florida art also grew.

Frankel always loved art. As a kid growing up in Brooklyn, oil paintings lined the walls of his uncle’s home. His family’s relocation to Hollywood, a city between Miami and Fort Lauderdale, added to Frankel’s awareness of art. The semi-tropical landscape of 1940s Florida was pristine and beautiful, and this was the setting in which Frankel spent his formative years.

In college, prints of Vincent Van Gogh’s Starry Night, Winslow Homer’s Eight Bells and Andrew Wyeth’s Christina’s World were hung in Frankel’s room. He read poetry, and the three images that kept watch spoke to him in the same way as Emily Dickenson and Robert Frost. The seeds were planted early in him for a life of art appreciation.

After an internship at Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami, Frankel served as a battalion surgeon with the Third Marine Division in South Vietnam. He later practiced orthopedic surgery in upstate New York but missed Florida. Returning in 1980, he became board certified in emergency physician and soon bought his first Florida painting.

The beautiful life woven into the fabric of Florida paintings attracted Frankel while he was in the thick of his medical career. However, that sense of arrival in a land of leisure that seemed devoid of personal responsibility would have to wait. Still he was beckoned by a topography suggesting escape, renewal and possibilities. This place was a carefree haven. This place was Paradise. The art of Florida reinforced those ideas. The substance of art has informed Frankel’s identity.

After World War II, and certainly by the early 1950s, Florida began to change. There were numerous tourist attractions: parrot jungles and monkey jungles; botanical gardens and jungle gardens; alligator farms and reptile attractions; aquariums with dancing porpoises; underwater shows and glass bottomed boats, to name but a few. Mosquito control, air conditioning, network television, employment opportunities, and affordable housing attracted many Yankee transplants. These changes, of course, led to the modernization of Florida. Florida became less personal, in a way. Nevertheless, many Florida artists continued to focus on those areas of unspoiled nature.

Few artists had come to Florida prior to statehood in 1845. Early explorers, most notably William Bartram and Mark Catesby, gave us renderings from their 18th century natural history expeditions. The wildlife paintings of Titian Peale and John James Audubon included landscape elements in the early 1800s. John Rogers Vinton painted The Ruins of the Sugar House in 1843; sketches of landscapes from the colonial period also exist. A landscape tradition in Florida took hold as Northerners discovered this tangled, fecund, and steamy place; it was particularly alluring after the Civil War. By the time oil tycoon Henry Flagler unfurled his east coast railway from the then cultural hub of St. Augustine in the 1880s, this exotic land had already captured artists’ imaginations. Although artists had painted in Florida before it was constructed, Flagler’s Ponce de Leon Hotel included a row of studios that constituted an artists’ colony where well-heeled visitors could socialize and buy paintings as fresh as Florida fruit.

Fred Frankel was not so interested in the modern landscape painters of that time who were carrying on an artistic tradition, whose Luminist paintings harkened back to Manifest Destiny. Recognized artists, including Martin Johnson Heade, Hermann Herzog, Louis Remy Mignot, Winslow Homer, William Morris Hunt, George Inness, Thomas Moran, and John Singer Sargent had come to Florida primarily to paint, generally in their later years and often at the request of Henry Flagler. Sure, they contributed to the art about Florida, and their paintings are most often the ones associated with the Florida art genre. But how about those paintings created by indigenous artists, those who made Florida their home or who came seasonally? These overlooked, fallen-through-the-cracks painters are the artists who interested Fred Frankel.

Frankel purchased his first Florida painting in 1981; by Sam Stoltz, it depicted a flamingo and an egret flying side by side, over the Everglades. Enamored by this artwork, he soon acquired paintings by Emmaline Buchholz, Asa Cassidy, and Howard Hilder. These paintings gave him pleasure but they also piqued his curiosity; he wanted to know more. Who created these paintings? He wanted to know not just their names but also their biographies; even their temperaments interested him. What brought them to Florida? When and where did they paint, and with whom did they study? No books about Florida art had been written yet. By 1983, Dr. Frankel was well under way to putting the pieces together. One artist’s biography led to the next and this led to multiple tapestries that were, he discovered, sorted by locale and constituted the roots of a number of art clubs, many of which years later became fine art museums. He realized, too, that women were at the center of the formation of these guilds and that art making was both a genteel and empowering practice.

Buying his first painting put Dr. Frankel on his mission to understand the development of Florida art. “And so, it began, painting after painting, and day after day, in libraries about the state. For me it was really fun.” He adds, “Today if I have a notion, it’s the hope that the people of Florida will eventually learn about their artists and begin to celebrate their work.” He learned that thousands of academically trained artists worked in Florida between the years of his inquiry–1840 to 1960–and that most were lost to the mists of time. In fact, he says that if these artists constituted a pyramid, 99% would be supporting the few we know. “You will find world class art in Florida’s museums but almost nothing by Floridians,” he points out.

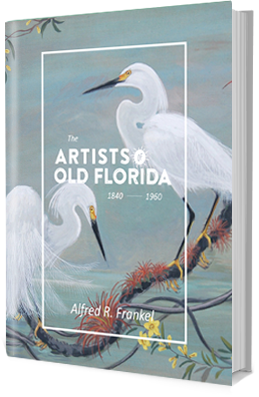

Frankel’s labor has culminated with two books. The Artists of Old Florida is an anatomy of Florida’s art history, a review of the corpus of Florida art. His Dictionary of Florida Artists, 1840-1960, contains the biographies of Florida artists; these are the artists who would call themselves Floridians, together with those who came to Florida year after year for the winter season. The Artists of Old Florida is available as a free download, while the Dictionary is not publicly available. Perhaps someday both books will be published.

As a surgeon, Frankel thinks of his research as an anatomy. It’s also groundbreaking, and through Dr. Frankel’s efforts scholars and collectors just recently began to discover the plethora of Florida artists.

Dr. Frankel defines Florida artists as:

1) artists who resided here in Florida

2) artists who came here annually

3) artists who belonged to a Florida art club

4) artists who listed in Florida telephone directories

5) artists who exhibited at Florida State Fairs

6) artists who were employed by the WPA and the Florida Art Project

He further explains: “Artists who came here once or twice and painted a view are not Florida artists, although when it comes to artists like Homer, or even Andrew Wyeth, you have to recognize their work here. Wyeth had family in Palm Beach and was an early member of the original Florida Watercolor Society.”

Fred Frankel’s research has informed Sam and Robbie Vickers of Jacksonville, who are recognized as the original collectors of Florida art, and Hyatt and Cici Brown of Ormond Beach, who came to the scene later but bought voraciously to also establish an encyclopedic collection. Their stellar collections and those of many others would be less complete without Dr. Frankel’s efforts. Others have built mature collections of Florida art; Scott Schlesinger and Earl Powell come first to mind. Their fascination with the genre stemmed from having discovered the Highwaymen, those African-American landscape painters about whom I wrote the seminal book and with whom Dr. Frankel’s research ends. Both collectors have commented that the paintings are reminiscent of the Florida of their youth, and from their Highwaymen paintings they each ventured to less pedestrian art, to paintings by notable 19th century artists made when the state was hardly habitable below the St. Johns River. Collections became increasingly comprehensive as lesser-known 20th century artists were recognized, showing the effects of the burgeoning state.

Mr. Schlesinger comments about Frankel’s labor: “Fred is unflagging and persistent, a passionate man who, in addition to being a man of science and medicine, values beauty as a co-equivalent essential for life. He speaks about the artists he discovered in different regions of Florida as if they were his family, because he has gotten to know them and love them.”

Gallerist Lisa Stone observes, “He forged ahead with patience and persistence to create an essential document. Fred didn’t reinvent the wheel; he went way beyond the obvious to establish a thorough history of Florida art.” Museum curators, collectors of all stripes, art dealers, along with historians and scholars have found, or will find, Fred Frankel’s research invaluable.

If we consider the nature of Florida art as a jigsaw puzzle, Dr. Frankel’s contribution is paramount to putting the pieces together.

Gary Monroe

© 2017